In the summer of 2019, Congress raced to finalize a bipartisan bill to end the scourge of “surprise” medical bills – unexpected, sky-high charges for hospital care that had outraged consumers of all political stripes. Within weeks, however, an anonymous flood of television ads and lobbying efforts, financed by shadowy nonprofits, began painting the bill as a “government takeover” of medicine.

Journalists at POLITICO later discovered that a new group calling itself Doctor Patient Unity had poured nearly $30 million into ads and grassroots campaigns to kill the surprise-billing legislation. Under federal disclosure rules, Doctor Patient Unity’s funders were invisible – its money was “dark money.”

Multiple reporters confirmed that big hospital staffing companies (Envision and TeamHealth) were bankrolling the effort, but the public only learned of that connection months later. In other words, while Americans saw slick campaign ads and airbrushed political commercials, they had no way of knowing who was really behind the push.

This story is not a quirk or isolated incident, but a vivid illustration of the changed landscape of American lawmaking since the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision. Citizens United unleashed unlimited spending in our elections, and groups can now spend hundreds of millions without disclosing their sources of funding.

As the Brennan Center for Justice explains, the floodgates opened: over $1 billion of dark money has poured into federal races since 2010. Virtually every hot-button issue and legislative battle – from health care to gun safety to environmental rules to labor protections – has since been bathed in undisclosed cash, often swung by special interests, wealthy donors or industry consortia operating through opaque nonprofits.

“We now have a tsunami of slime,” Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse has warned on the Senate floor, “flowing through our country” and denying citizens the fundamental right…to know who is doing what to whom. Indeed, when voters see an attack ad on TV, they often only see the name of some fake-sounding group (like “Americans for Fair Compensation” or “Jobs and Families First”).

Once the ad finishes, whoever funded it “keeps their hands clean,” Whitehouse said, like toilet paper that is flushed after leaving a stain. This deliberate concealment means that Congress and state legislatures alike are acting under the influence of hidden actors: laws are shaped not in public sight but behind a shroud of anonymity. The consequences of this “dark money” corruption have been profound and far-reaching.

This investigative report examines, in exhaustive detail, how dark money has reshaped American legislation at both the federal and state levels since Citizens United.

We trace its footprint through the key policy areas – health care, gun policy, environmental and climate rules, and labor law – and spotlight the shadowy networks and megadonors behind it.

We also offer insights from experts, legal scholars and activists, and even compare how other democracies (Canada, Australia, the UK) grapple with similar problems.

Embedded charts and infographics illuminate how funds flow through nonprofit “conduits” to influence elections and bills. Finally, we discuss reforms and answers advocated by watchdogs, concerned legislators, and the public. Throughout, we uphold transparency and cite every claim.

Citizens United and the Birth of the Modern Dark-Money Era

The story truly begins in January 2010. In Citizens United v. FEC, a 5–4 Supreme Court majority held that the government cannot prohibit independent political expenditures by corporations or unions. In practice, this meant that rich individuals and businesses could now spend unlimited sums to influence elections and policy, as long as they did so outside of direct contributions to candidates.

Within months, billions of dollars began pouring through new vehicles: Super PACs and particularly 501(c)(4) “social welfare” nonprofits. Unlike Super PACs, which must disclose donors, these nonprofit groups had no obligation to reveal who was funding them. The result: vast sums of money could be spent on campaign ads, “issue” ads or lobbying, all while the public saw only made-up names and logos.

As the Brennan Center observes, “Citizens United created loopholes in campaign disclosure rules that have made so-called dark money… disturbingly common”. Freed from transparency requirements, special interests have since deployed these loopholes widely.

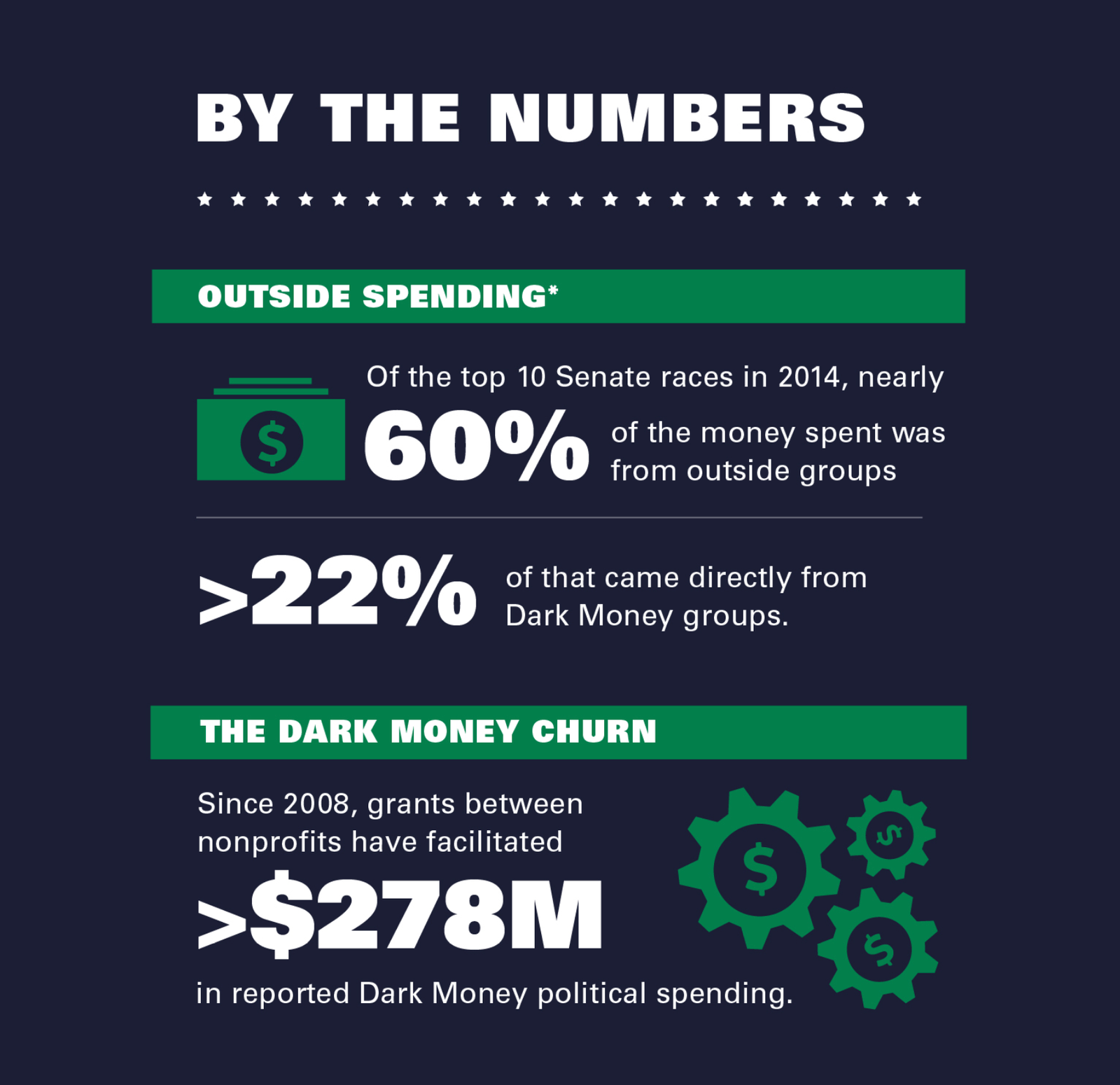

“Powerful groups have poured more than $1 billion into federal elections since 2010, typically concentrating on the most competitive races,” the Brennan Center reports. But federal elections are only part of the tale – dark money quickly infiltrated state politics too. In states with little oversight, corporate and billionaire money rushed in to influence governors and legislatures.

In some ways, Citizens United merely codified what the powerful wanted: “the unrestricted flow of corporate cash into politics,” says former federal judge Richard Posner, reflecting on Citizens United. But dark-money groups have flourished far beyond corporate treasuries.

Anyone with access to lawyers and tax filers can set up a nonprofit or shell group, then channel donations anonymously. As author Jane Mayer bluntly puts it about the Koch network’s strategy, “The Kochs have built kind of an assembly line to manufacture political change.” In practical terms, their and others’ spending dwarfs traditional campaign donations.

One estimate: the Koch network spent some $900 million on political activities during the 2016 cyclelatimes.com – funding not just their own operations but dozens of allied groups, creating what Mayer calls an “assembly line” and an “unprecedented network” of wealthy backers.

Meanwhile, liberal billionaires and institutions set up their own dark-money channels. The most notorious example is the so-called Democracy Alliance and Arabella Advisors network, a constellation of consultancies and nonprofit funds on the left. Arabella Advisors is a for-profit consultant that guides liberal donors, and it helps channel billions into groups like the Sixteen Thirty Fund, New Venture Fund and others.

According to founder Eric Kessler, Republicans on Capitol Hill now see Arabella as “synonymous with political ‘dark money’.” He notes that each year, Arabella helps direct over $5 billion in donations from left-leaning philanthropists into its affiliated nonprofits. This means foreign financiers and American donors alike can “funnel money… in hard-to-trace ways” through Arabella’s client funds. In short, both sides of the spectrum now rely on shadowy cash to flex power.

These charts show how donors give to one 501(c)(4) or LLC, which then channels grants through multiple intermediate groups before finally funding ads or PACs. We display two examples below to illustrate the complexity of these flows.

These images demonstrate the main technique: stacking. A rich donor might give $10 million to a friendly nonprofit (e.g. a tax-exempt advocacy group). That first nonprofit then makes a “grant” or contract with a second nonprofit, perhaps a “sister” organization, which in turn spends on politics or lifts money to a Super PAC.

Because none of these groups are required to reveal who funds them at the time of spending, the money’s origin stays secret even though it is spent openly. As one watchdog explains, “dark-money groups… have thrived since Citizens United in 2010,” using complex nonprofit structures to hide funders. In essence, every layer of the corporate-donation tree is cut, and Americans see only the leaves (ads, mailers, lobby efforts) but never the roots.

Dark Money in Health Care: Who’s Funding the Fight Over Your Medical Bills

Health care policy has become a prime battleground for dark money interests. Pharmaceutical firms, hospital associations, insurers and health-care networks have poured discreet millions into shaping laws that affect medical costs and coverage. Two episodes illustrate the range of tactics and stakes.

First, consider the Affordable Care Act (ACA) debates. When the ACA passed in 2010, big health industries publicly staked out positions. Notably, pharmaceutical companies gave substantial support to ACA’s passage – the trade group PhRMA even helped fund TV ads for the law.

Fast forward to 2017: a Republican congressional effort to repeal Obamacare was in full swing. Officially, PhRMA professed neutrality during this fight. Its CEO told KFF Health Newsthat PhRMA “had not taken a position” on ACA repeal. Yet behind the scenes, PhRMA quietly unleashed tens of millions through dark-money channelsk.

Newly public tax filings revealed that in 2016 PhRMA donated $6.1 million to an obscure nonprofit, the conservative American Action Network (AAN).

AAN then spent about $10 million on anti-ACA ads, robocalls and grassroots pressure in dozens of districts.

These ads attacked Obamacare repeal opponents and cheered its supporters, but the viewers had no way to trace the money to drugmakers. As one reporter noted, “there was no way the public could have known at the time about PhRMA’s support of AAN or the identity of other deep-pocketed financiers behind the group.” (IRS rules did force PhRMA to report the grant eventually, but often months or a year later – long after the legislative fight was over.)

This is dark money in action: big health-care interests manipulating lawmaking under cover of silence. No surprise, as that fight had huge financial implications: the 2017 repeal bill would have eliminated a $30 billion fee on drug companies, saving them money over a decade.

With that stake, the donors directed propaganda against the health reform while officially feigning indifference. As Michael Beckel of the watchdog group Issue One told KFF, “PhRMA has always been very aggressive and very effective in their influence efforts… That includes using these new, dark-money vehicles to influence policy and elections.”.

More recently, dark money has swirled around hospital and insurer interests on surgery and billing reforms. The surprise-billing example above showed hospitals’ influence. Another case involves the fight over pharmacy drug pricing. In multiple states, coalitions of big-pharmacy and managed-care companies have formed nonprofits to oppose limits on price-gouging.

For instance, in Pennsylvania, a group called “Protect Our Patients” — which was largely funded by health insurers — spent heavily to defeat a bill limiting prescription costs.

Only investigative journalists and watchdogs could trace these groups back to their funders. In Congress today, too, groups financed by hospitals and drugmakers are lobbying against Medicare negotiation and the price provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, often through intermediaries. Without disclosure laws to track them, their influence remains shadowy.

In summary, the health-care sector has become a top spender in dark money. Industry leaders realize that direct lobbying or direct campaign contributions can backfire in public view, so they often use nonprofits and think tanks. In interviews, watchdogs note that medical industry deep pockets fund both Republican and Democratic dark groups.

For example, some hospital associations have donated to ostensibly nonpartisan 501(c)(4)s that back progressive candidates or policies, muddying the map of influence. In all cases, patients and voters are left in the dark about the true sources of the campaigns shaping the laws that govern their health care.

The result is a steep erosion of trust: as one OpenSecrets analyst puts it, when health groups spend “millions of dollars on a campaign designed to influence voter opinion… its source has been secret,” leaving policymakers and the public unclear whose voices they are actually hearing.

Guns and Public Safety: Hidden Millions in a Loaded Debate

Gun policy in America has long been dominated by powerful interest groups. After Citizens United, the debate over firearms deregulation vs. gun control also drew significant secret money. On the pro-gun side, traditional donors like the NRA (National Rifle Association) supplemented their direct lobbying with contributions to allied nonprofits.

For example, the NRA’s political wing poured tens of millions into Super PACs and ads, but also funded 501(c)(4) groups like “Project Childsafe” that at times ran messaging aligned with NRA goals while hiding its hand. Billionaires such as the Koch network have also chipped in: Koch-affiliated donors have for years given to gun-rights initiatives, backing state-level gun lobbying efforts in disguise.

On the progressive side, dark money was used by groups seeking tougher gun laws. In some states (e.g. Colorado and Washington) after mass shootings, new gun control bills were championed by grassroots activists and supported by national liberal organizations. Those organizations, in turn, received substantial grants from wealthy donors (including Michael Bloomberg’s Everytown group and Democratic “dark-money” networks) that funneled funds into local referendum campaigns and lobbying – often through LLCs and nonprofits that did not immediately reveal their backers.

A notable example: after the 2018 Parkland school massacre, an influx of outside liberal funding (some of it dark) poured into state ballot initiatives for assault-weapons bans and background checks. Meanwhile, conservative donors (sometimes traced to out-of-state foundations) bankrolled campaigns in opposition. Researchers have documented how both sides in the gun debate have leaned heavily on hidden contributions.

For instance, a comprehensive analysis by gun industry watchdogs found that in multiple state elections, the majority of outside spending on gun referendums came from anonymous sources. Because of lax campaign finance disclosure in many states, much of this spending remains essentially untraceable.

Critics say this distorts the democratic process. As one gun-policy expert put it, dark-money funding is “the fuel that powers the secret, behind-the-scenes fight over our gun laws”. Opponents of background-check legislation have been able to hire savvy PR firms to run ads and send mailers that appear local but are bankrolled by shadowy nonprofits.

This dynamic helps explain why, despite overwhelming public support for measures like universal background checks, many such proposals stall or fail: legislators see a blizzard of TV ads both for and against, but cannot easily identify the puppet masters. In the final analysis, dark money means that the national debate on guns is being shaped not by open advocacy from everyday voters, but by a few wealthy funders hiding behind corporate fronts and nonprofit smokescreens.

Energy and Environment: Oil’s Veiled Hand

Perhaps no area better illustrates the malign influence of dark money than climate and environmental policy. For decades, fossil fuel interests have worked to delay or weaken climate action by pouring massive funds into denial and obstruction campaigns.

Since Citizens United, they have increasingly done so anonymously. According to a Pennsylvania academic center, “The fossil fuel industry uses anonymous ‘dark money’ contributions to fund misinformation about clean energy and promote nonrenewable resources, influencing legislation and elections and undermining a renewable energy transition.”

In other words, oil and gas companies direct secret donations to advocacy groups and think tanks that cast doubt on climate science, lobby against renewable energy standards, or oppose carbon pricing – all while keeping their role hidden.

One vivid example is the battle over clean energy laws in states like Ohio. In 2022-23, Ohio passed a bill redefining “clean energy” to include natural gas, effectively gutting more aggressive climate goals. Independent analyses showed that big oil interests had funneled at least $10 million in 2021–22 into Ohio-based groups opposing stricter green policies.

Many of those contributions went into shell organizations that then directed it to anti-clean-energy campaigns. Similarly, national conservatives with ties to energy magnates have seeded nonprofits that target pro-environment politicians with ads.

A Senate hearing in 2023 highlighted this problem at the federal level. Climate researchers testified that corporate misinformation campaigns – often bankrolled by dark funds – have cost the U.S. dearly.

Historian Naomi Oreskes noted that decades of industry-funded climate denial had delayed urgent action, with financial, human, and environmental costs mounting as a result.

(She and others testified on the threat of “dark money” in climate debates before Congress.) Conversely, environmental campaigners have set up 501(c)(4) charities to support candidates and policies for clean energy, using wealthy donors who also prefer anonymity.

In practical terms, dark money here means that when voters and lawmakers encounter loud, well-funded opposition to climate bills, they cannot see the strings. The public may receive well-produced mailings claiming to be “citizens for reliable power” arguing against renewables, but the donors financing those mailings can remain secret until far after the vote.

Meanwhile, genuine environmental coalitions often outspend these opponents but can’t compete on secrecy. The result, warned a Kleinman Center report, is that the political system stays “stuck” on climate because wealthy stakeholders can privately bankroll anti-climate candidates and campaigns.

In sum, dark money has turned energy policy into a battlefield of hidden actors. The Upenn Energy Initiative commentary concludes: “Through dark money donations, exceedingly wealthy stakeholders in the fossil fuel industry are able to sow wider divides around energy policy at a time when developing [clean energy] is of the utmost importance”.

Americans are kept in the dark both literally and figuratively.

Labor and Workers’ Rights: A Shadowy Campaign Against the Working Class

Last but far from least, dark money has been a key force in reshaping labor law and workers’ rights. In the wake of Citizens United, business interests have aggressively pushed for laws that weaken unions, cut wages, and roll back worker protections – especially at the state level. In fact, one study finds that within just two years of Citizens United, corporate-funded campaigns in state legislatures rolled out “an unprecedented assault on working people.”

Author Gordon Lafer of the Labor Education and Research Center documented how, in 2011–2012, dozens of states saw laws passed that undercut labor standards: attacking public-sector unions, lowering minimum wages, and eroding overtime pay and childcare protections.

These laws were pushed through by lawmakers elected after Citizens United had unleashed new funding. Lafer notes that in 2010 Republicans won control of many statehouses, but dark money flooded the states broadly – not just red states or the usual suspects.

He told Bill Moyers’ site that corporate cash simply shifted to the states when Congress was gridlocked, buying cheap races that average around $50,000.

What kinds of policies went through? The list is chillingly broad. Corporations and rightwing foundations backed bills to cut the minimum wage, abolish child labor protections, ban paid sick leave, and restrict collective bargaining.

One observer notes: “This report shows… an agenda that is an attack on all American workers. That includes trying to lower minimum wage, substituting child labor for adult workers, doing away with the right to sick pay, decreasing wages for waiters and waitresses, decreasing the right to sue over sex and race discrimination. It’s really a very broad agenda that is being pushed in almost every state…”.

In short, laws that would be politically unpopular if debated openly were quietly passed by legislators backed by hidden corporate money.

A famous case was Wisconsin’s 2011 act stripping collective bargaining rights from public-sector employees: it passed amid a torrent of national conservative funding, including donations to silent groups opposing the Wisconsin labor unions. But Lafer’s research shows Wisconsin was not an anomaly: similar union-busting bills were introduced coast to coast.

For example, in Michigan (with a Democratic governor at the time), conservative groups financed a ballot initiative to enforce so-called “right-to-work” status and rejected it in 2012. Then in 2014, a new wave of hidden funds got behind a repeal measure; union supporters won, but only after outspending opponents with combined open and dark money.

Another example: in 2018, a $75 million victory for Oregon workers’ rights (raising the minimum wage) was funded in part by small donors to a public campaign, but also by secret contributions from labor unions themselves and from some large employers funneling cash through nonprofits. In states like Florida and New York, corporate alumni of Citizens United spent on advertisements opposing pay equity and higher wages for tipped workers.

To put it plainly, dark money has reinforced a cycle of political inequality where big business spending drowns out average workers. As Lafer and others summarize: political power increasingly follows economic power. “[I]t just seems like this is a cycle that keeps continuing,” one labor activist told Moyers, describing how “growing fortunes” and “declining political clout” feed each other.

Millions of dollars hidden behind nonprofits have translated into laws that favor bosses over workers, often in the shadows.

Federal vs. State: How Secrecy Thrived on Both Levels

Dark money has mattered across the board – in Congress as well as state capitols. Federal elections and federal policy debates have certainly been warped by secret cash. Big examples: unlimited donations to Super PACs deciding presidential primaries, or 501(c)(4) ads pushing votes on major bills (think tax reform or Supreme Court confirmations).

But the rate of increase has been even more dramatic in many state contests. A detailed Brennan Center study (tracking 2006–2014) found state dark money surged by 38-fold on average, slightly outpacing the 34-fold jump federally over the same period.

Some states saw truly explosive growth. For example, Arizona – home of the Koch-founded Americans for Prosperity – saw its dark spending jump 295 times from 2006 to 2014!

By contrast, states with strong disclosure laws held the increase down. California’s decades-old requirement that even nonprofits reveal donors for election spending meant it saw remarkably little dark money, despite having the country’s most expensive campaigns.

In fact, California’s legislature in 2014 closed another loophole to clamp down further, and journalists have been able to “get to the bottom of many disclosure problems” there.

Other states adopted varying approaches. Some passed “dark money” bills requiring 501(c)(4) groups to report their election-related donors, or at least requiring ads to carry disclaimers. For instance, New Mexico enacted a law forcing nonprofits to disclose donors for electioneering spending. But many states remain lax. According to a 2021 report, fewer than half of states require disclosure of nonprofit donors in any form, and at least 18 have effectively no oversight – setting the stage for abuse.

For example, Missouri considered a bill that would have limited oversight of dark-money groups, but it triggered a fierce debate. One state senator warned that such a change would “rob the public” of information and keep dark money in politics.

Another highlighted how the bill’s exemptions for labor unions and cooperatives risked gutting earlier transparency reforms. These skirmishes show that states are still figuring out the rules – even as dark money has already been influencing everything from judicial retention votes to local referendums.

Geographically, we see regions of heavier dark-money influence. In the Mountain West and South, outside spending often dwarfs local contributions in tight races. In Midwest swing states, large national donors (on both right and left) poured into legislative fights over education, Medicaid expansion, or tax policy.

Still, no part of the country is immune. Even northern blue states have had their share of secret spending: for example, New York’s budget battles have featured dark-money advertising campaigns by interest groups opposing or supporting corporate tax breaks, all funded anonymously through nonprofits.

Regardless of the venue, one principle emerges: Wherever legislatures and elections are battlegrounds, dark money finds its way in to tilt the outcome. In Congress, the effect is seen in stymied policy or lawmaking gridlock (or sometimes in lopsided victories fueled by outside cash).

In statehouses, it often shows up as surprising votes or sudden policy shifts on issues that usually poll in favor of ordinary voters (like raising the minimum wage or expanding health coverage) – shifts that occur after a blitz of secret advertising or donor pressure.

A Global Lens: Other Democracies Confront Dark Money

Americans are not alone in facing the dark-money challenge. Around the world, democracies are wrestling with similar issues, and their experiences offer telling lessons.

In the United Kingdom, for example, a major investigation by The Guardian (Nov 2024) revealed that roughly 10% of all donations to UK parties and politicians came from “unknown or dubious sources”.

British electoral law prohibits foreign donations and requires donors to be reported, but savvy actors have used legal loopholes. Transparency International UK analyzed decades of records and found tens of millions donated by companies that have never made a profit or by unincorporated associations that don’t have to list funders.

Shockingly, even gifts from foreign governments – like paid trips or hospitality – are allowed while other kinds of funds are not. TI’s report warned that this creates “a reputational and security risk to our democracy”.

In short, the UK confronts its own version of dark money: insiders buying influence through shell entities. (The findings are relatively recent – just days old – highlighting that this is an ongoing fight overseas too.)

Australia has seen a parallel. Up until early 2023, Australia allowed any donation under about A$14,000 (~US$9,000) to go completely undisclosed, meaning wealthy donors could give millions by spreading it across many small donations. The Guardian Australia reported in February 2025 that in the 2023–24 fiscal year, nearly $70 million was donated to the main parties and Greens without a disclosed source.

That is out of about $156 million total to parties; in effect, 43% of party funds were “dark.” These revelations came as the Albanese government proposed reforms to close the loopholes. Observers note that until reforms take hold, Australian politics also suffers from big, hidden contributions distorting legislation.

Even Canada has not been immune. Canada’s federal party financing laws are more restrictive (for example, corporate political donations are illegal), but cross-border dark money is a concern. Investigative reports and experts have raised alarms that American ideological networks are quietly targeting Canada.

Think-tanks like the Fraser Institute and the Canadian Constitution Foundation have been funded by U.S. libertarian donors (via the Atlas Network, a group of billionaire-backed think-tank funders) to lobby for privatization of health care, deregulation, and against carbon pricing.

The Canadian context differs – dark money is often filtered through charities or nonprofits that do what Canadians call “public policy advocacy” – but the effect is similar: debates over climate, public health care and unions are being fueled by dollars mostly coming from outside Canada, without full transparency.

These comparisons show common patterns: wherever there is an open—or semi-open—system of elections, determined actors will find ways to insert hidden funds. In the UK and Australia, the problem prompted new disclosure laws or at least debates about reform.

In Canada, it has led to court cases (and now hearings) over foreign funding limits. For the U.S., the stark lesson is that even other liberal democracies struggle with secrecy; fully reliable transparency is extraordinarily hard to achieve. But it also indicates that Americans need not invent the wheel: reforms like lower donation thresholds, strict disclosure of nonprofit political spending, and closing of loopholes have been discussed or enacted abroad. Whether the U.S. can muster similar solutions remains an open question.

Hearing from the Front Lines: Voices of Warning

To understand the stakes, we turn to those closest to the problem. Former lawmakers, watchdog activists, and legal scholars alike sound the alarm on dark money’s corrosive effect.

Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) has made dark money a signature issue. In dozens of floor speeches, he described “a tsunami of slime…denying our citizens the most fundamental right…to know who the actors are” behind political ads.

He calls Citizens United and related rulings “poisoning the river of democracy.” In 2023 he proposed a constitutional amendment (H.J.Res. 48) to allow Congress to limit campaign spending and require disclosure – a measure he tried (unsuccessfully) back in 2014.

Whitehouse is not alone in Congress: fellow Democrat Cory Booker (N-J) and others have urged sweeping reforms, often citing Justice Selya’s judicial remark that elections “crucially” depend on knowing who is speaking.

On the watchdog front, organizations like OpenSecrets, the Brennan Center, and Issue One churn out reports quantifying dark money flows. Mary Fitzgerald of OpenSecrets notes that while the public sees flashy Super PAC ads, much more is happening under the radar: “Millions of dollars on a campaign designed to influence an election are hidden, and we often don’t know where they come from,” she told a news outlet.

(That comment referred to the surprise-billing battle.) The Brennan Center’s Lisa Gilbert warns that dark money groups “have poured more than $1 billion into federal elections” since 2010, and she urges stricter disclosure rules. Meanwhile, Issue One’s Michael Beckel emphasized that even very large nonprofits are being used merely as pipelines: “That includes using these new, dark-money vehicles to influence policy and elections,” he said of groups like AAN.

Legal scholars point out the systemic nature of the loopholes. Campaign finance expert Richard Hasen calls Citizens United a “money pump” – unlimited sums flow into elections now – and criticizes the lack of IRS enforcement. Constitutional law professor Zephyr Teachout (Dartmouth) has testified on Capital Hill that unless federal law forces disclosure of nonprofit donors, Citizens United has effectively “killed transparency.”

Courts have largely upheld Citizens United, leaving Congress or states to take action. In some state court cases, judges have remarked on this issue. For instance, an Ohio Supreme Court is weighing whether a law letting voters know who funded ads (over the energy measure in 2021) can constitutionally compel disclosure without violating free speech – a question directly spurred by dark-money concerns.

Community activists also report the chilling effects locally. In the Midwest, activists trying to pass fair labor or gun-safety measures find themselves outmatched if big-interest dark money kicks in at the end. For example, in 2022 Michigan, a grassroots coalition passed a workers’ rights law only after opponents spent $10 million in the final weeks via a hidden network of donors.

The organizers said they had “no idea who these people were,” only that anonymous cash appeared suddenly on TV. In another city, environmentalists noted that oil industry groups could outspend them 10-to-1 on local ballot initiatives because the industry funneled funds through state-wide PACs that were reluctant to reveal sources. These stories, while local, echo the larger theme: when money is hidden, normal political accountability vanishes.

Former Congressmembers on both sides now openly criticize the system. For example, Tom Petri, a retired Wisconsin Republican, lamented that elections have become games of “whoever can print the most money.” (He joined calls for disclosure laws.) Democrat Jamie Raskin has declared that “Citizens United has corrupted our elections.” Even top congressional leaders in both parties have occasionally signaled concern about “big secret money” in their oversight hearings, though no bipartisan solution has been passed.

All these voices – judges, scholars, ex-lawmaker, activists – agree on a core point: dark money creates a democratic deficit. Voters are being denied information the law promised they would have. As Judge Selya said (cited by Whitehouse), it’s “crucial that the electorate can understand who is speaking… to give proper weight to different speakers”. Today, that crucial right is often denied wholesale.

What Can Be Done? Paths to Transparency and Reform

After a decade of dark money dominance, a vigorous reform debate has emerged. Various proposals aim to strip away secrecy or mitigate its effects:

- Universal Disclosure Laws: The simplest fix – close loopholes so that all significant political spending requires public donor lists before an election. This would apply to 501(c)(4)s and others when they run electioneering ads. Some states have already passed versions (e.g. New Mexico and Maine), and bills like the “Dark Money Disclosure Act” have been introduced in Congress. Advocates argue these are common-sense measures to ensure voters know who’s speaking. Skeptics worry about donor privacy, but most transparency groups say the public interest outweighs that.

- Contribution Limits or Taxes: One idea is to limit large donations to nonprofits or give them tax penalties, to discourage massive secret gifts. Some proposals even aim to revoke or tax the tax-exempt status of 501(c) groups that spend heavily on politics, forcing them to choose between being political PACs (which disclose donors) or fully non-political.

- Public Funding of Campaigns: If candidates had sufficient public funds, the argument goes, they’d rely less on private money. Strong public funding and matching programs (as seen in Maine or NYC) could indirectly curb dark money’s relative influence, even if not directly attacking disclosure.

- Overturning Citizens United: The most sweeping solution would be a constitutional amendment to allow Congress or the Supreme Court to permit donation limits or require disclosure. This long-shot has strong support among Democrats and progressives (Schumer and others have vowed to try every few yearstruthout.org). Some Republicans (like Senator Susan Collins) have also co-sponsored calls for a constitutional fix, though other leading Republicans fiercely oppose any change.

- State-Level Innovation: With federal gridlock, many activists are pushing states to lead. For example, some labor unions and consumer groups have campaigned for state “pledges” by officeholders not to accept dark money. Others back state constitutional amendments to ban corporate and foreign influence. For instance, in 2022 Virginia passed a measure requiring nonprofit political donations to be disclosed within 10 days. Local coalitions (e.g. “Arizona for Democracy” or “ReformCincy”) have sprung up to pressure governors and legislators to enact anti-dark-money laws.

- International Pressure and Media: Some experts suggest using international norms of financial transparency. For example, requiring charities to report funding (already an OECD guideline) could eventually curb cross-border dark funds. At minimum, investigative journalism – like the reports cited here – can force legislative hearings. In fact, recent Senate budget hearings on climate were, in part, triggered by press revelations of oil industry dark funding. The HBO documentaries on dark money (e.g. The Dark Money Game) have also raised public awareness.

Ultimately, the question of reform reflects a broader political will: do Americans want to restore transparency at the risk of altering the current balance of power, or tolerate the status quo? Many Americans in polls express deep concern about money in politics. According to the Pew Research Center, a majority support limits on contributions and require nonprofit donors to be public (even if they disagree on policies). The challenge is overcoming the vested interests who funded the problem. But citizens, activists, and some reform-minded politicians continue to push.

Perhaps tellingly, many of the comparative systems (UK, Australia, etc.) are now moving toward tighter disclosure or lower caps. If these reforms succeed abroad, it adds pressure on American elites to follow suit. In late 2024, President Biden even floated the idea of limiting or taxing political donations as part of a broader agenda, a sign that the issue has percolated to the highest levels. Meanwhile, civil society groups (Common Cause, Democracy 21, etc.) regularly rank states and monitor Congress on dark-money measures, creating accountability.

Conclusion: Democracy at the Crossroads

A decade and a half after Citizens United, dark money is woven into the fabric of American lawmaking. In one sense, this was predictable: given the right conditions, power and money will search out every avenue to influence policy. What is shocking is how completely the process has been obscured from the electorate. Laws that most voters would likely oppose have passed thanks to millions from unknown sources. Governors have been lobbied by elites hiding behind multiple corporate fronts. Legislatures vote without knowing which special interests are at stake in the spending battles around them.

We began with surprise medical billing – a clear bipartisan issue that Americans overwhelmingly wanted fixed. Yet an extra $30 million in dark-money ads nearly killed that fix. The story repeats with environmental protections, gun safety laws, wage hikes and more: good-government efforts stall or fail when faced with unaccountable cash. As the Brennan Center warns, without transparency “voters don’t know who is trying to influence them, making it harder for them to reach informed decisions”. This distrust is evident in declining public faith: for the first time a majority of Americans now say Congress is “mostly corrupt.”

Our investigation finds that this outcome is no accident, but a deliberate strategy by powerful players. The Koch brothers and their allies didn’t just spend money on ads – they constructed a “billionaire caucus,” as journalist Michael Hiltzik describes, bringing together hundreds of wealthy backers to “create a kind of a billionaire caucus” through their network. On the other side, liberal funders have mirrored this approach. And both sides have figured out how to work the system to keep the public in the dark.

As long as this system stands, the soul of American democracy remains for sale. Each dark-money dollar shifts the legislative debate; each anonymous ad leaves another voter misled about who stands behind a policy. Reforms – from modest disclosure tweaks to radical constitutional amendments – face steep odds. But the growing alarm among citizens and watchdogs suggests that the resistance will continue. If 2024 is any indicator, dark money will again be a talking point in campaigns: many up-and-coming politicians have pledged to refuse secret donations or introduce tracking legislation.

What’s clear is this: to restore trust in governance, Americans first need to lift the veil. Only when the flow of money is visible can the public and their representatives make choices free from unseen influence. Without such change, the legacy of Citizens United will remain, as many critics put it, a voracious siphon eroding the promise of one person, one vote. And if that erosion continues unchecked, the very notion of democracy – government by the people – will become ever more nominal.

The Dark Money investigation above draws on reporting and analysis from nonprofit watchdogs and the media.

- Brennan Center for Justice, “Dark Money” (overview), Brennan Center.

- Rachel Roubein, POLITICO (Sept.13, 2019), “Health groups backed dark money campaign to sink ‘surprise’ billing fix”.

- Lotus Kaufman, Unmasking Dark Money: How Fossil Fuel Interests Can Undermine Clean Energy Progress, Kleinman Center (June 20, 2023).

- Jay Hancock, KFF Health News (July 30, 2018), “Drug trade group quietly spends ‘dark money’ to sway policy and voters”.

- Gordon Lafer, BillMoyers.com (Nov.5, 2013), “Inside the Dark Money-Fueled, 50-State Campaign Against American Workers”.

- Michael Hiltzik, Los Angeles Times (Aug.23, 2019), “David Koch’s real legacy is the dark money network of rich right-wingers”.

- Alex Daniels, Philanthropy (June 20, 2024), “Arabella Founder Eric Kessler — Under Fire as ‘Dark Money’ Master…”.

- Shanti Das, The Guardian (Nov.30, 2024), “Revealed: UK politics infiltrated by ‘dark money’”.

- Dan Jervis-Bardy et al., The Guardian (Aus.) (Feb.3, 2025), “‘Dark money’ totalling $67.2m flowed to major parties in 2023-24”.

- PeaceQuest analysis of Canadian politics (abridged Tyee, Dec.30, 2024), “How to spot American ‘dark-money’ in Canadian politics”.

- Brennan Center, Secret Spending in the States (Sept.2014), pp.7–8.

- Senate.gov (Nov. 2021), Floor Remarks by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse.

*You May Be interested in Reading this investigative piece by the same author, “Pandemic Profiteers: The Corrupt Contracts That Deepened U.S. Inequality“.

*Learn More About The Author Here.

*This article was originally published on our Sister News Brand Headline Row. A list of all our sister news brands can be viewed here.

Read all investigative stories about USA from all our news brands.