This is the story of how Windrush scandals rocked Britain and why Windrush Reparations came into existence.

June 22, 1948 – the arrival of the Empire Windrush at Tilbury Docks marked a hopeful turning point. Britain, war-weary and in need of workers, welcomed Caribbean migrants as citizens.

The ship carried 1,027 passengers (and two stowaways) from Jamaica to London.

More than 800 of them gave a Caribbean country as their last place of residence.

These new arrivals were officially British subjects under the 1948 British Nationality Act, entitled to settle and work in the UK.

The Windrush’s arrival became symbolic of an invitation: Britain needed to be rebuilt, and its empire citizens answered that call.

Historic photograph of workers at Castries harbor, St Lucia, circa late 1940s, representing the Caribbean origins of many Windrush passengers.

The newcomers faced challenges: hundreds had no homes initially.

In fact, 236 of Windrush’s passengers with nowhere to stay were temporarily housed in a deep bomb-shelter on Clapham Common while local charities found rooms.

Many black immigrants endured racial prejudice in daily life. Over time, however, the Windrush generation became celebrated for helping to rebuild Britain. Peers in Parliament later praised them for their “invaluable role in rebuilding our country and public services in the aftermath of the Second World War”.

They staffed the newly formed NHS, drove trains and buses, built homes and factories – indeed, “our country would be greatly diminished if they had not come”.

Sports, music, arts and politics were all enriched by Caribbean-British families.

Today a permanent National Windrush Monument at London’s Waterloo Station stands testament to their contributions, funded by the UK government as a tribute to this generation.

From British Subjects to ‘Illegal Immigrants’

Decades after 1948, many Windrush-born Britons had lived nearly their entire lives in the UK, assuming implicitly their British citizenship remained secure.

Yet in the 2010s the government’s priorities shifted. In 2012, Home Secretary Theresa May announced plans for a “really hostile environment for illegal immigrants”.

Laws were tightened so that anyone without formal status paperwork would be denied work, housing or even a GP registration. In practice this policy swept up lawful residents.

“It stems from a policy…to make the UK ‘a really hostile environment’ for illegal immigrants,” explained the Guardian.

The burden of proof was effectively reversed: ordinary people had to prove their right to remain or risk being treated as unlawfully resident.

In reality, many Windrush-era migrants had never been issued passports or national ID cards when they arrived as children on their parents’ papers.

The Home Office had itself often failed to document their status. Human Rights Watch notes that these Caribbean-born Britons “after living and working in the UK for decades” found themselves suddenly “required…to meet impossible government requirements to prove their UK citizenship or residence rights”.

Without easy records (the Home Office even admitted destroying thousands of arrival landing cards in 2010), many could not readily produce ID.

Government itself acknowledged the chaos: a 2018 internal report (later leaked) concluded that every post-war immigration law from 1950–81 was aimed partly at reducing people with Black or brown skin allowed in Britain.

In short, decades of official neglect and lawmaking meant that former British subjects from the Caribbean were quietly being made “illegal” in their own country.

By 2017 journalists had begun to uncover the fallout. Investigations showed lawful long-term residents – some over 70 years old – being denied services or threatened with removal because they lacked modern papers.

Paulette Wilson, who had moved to Britain aged 10, suddenly received a Home Office letter classifying her as “an illegal immigrant” and promising deportation.

In her own words, the treatment “shook her sense of identity and belonging.” Although detained for a week and nearly deported, she was let go only at the last minute.

As HRW explains, “they lost jobs, homes, health care, pensions, and benefits. In many cases, they were detained, deported, and separated from their families.”

Voices of Victims: Personal Testimonies

Through media stories and public hearings, individual tragedies emerged. Paulette Wilson described the profound fear and heartbreak of her detention: “I felt like I didn’t exist… All I did was cry, thinking I wasn’t going to see my daughter and granddaughter again. I couldn’t eat or sleep.”

She still suffers from nightmares years later. Her case helped personalize the crisis.

Another victim, Ivan Anglin, had built a life in England over 35 years. In 1998 he was detained at Heathrow airport after a family funeral in Jamaica and given just two days to liquidate his home and belongings for a one-way flight back.

He and his daughter “felt like lambs to the slaughter,” he recalled later. “I did what they told me to do,” he said. The deportation exiled Ivan from his eight grown-up children in London. He quietly rebuilt a life abroad, but the pain remains.

His story, like many others, shows how utterly powerless Windrush victims became. Ivan’s daughter Patricia noted her father “missed out on the births of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, the funeral of his only son, and other close family members… He was a decent, hard-working person” – yet he was forced out.

Victims’ families also spoke out. Dexter Bristol’s sudden death in 2018 (he was 58) brought the scandal’s worst consequences to light. Having worked in construction and paid taxes for 50 years, Dexter was declared an illegal immigrant after losing his passport.

His mother Sentina Bristol demanded accountability: “We have not heard a word from anyone at the Home Office… They don’t really care.” The family received no condolence letter. In anger and sorrow she said plainly, “There is only one word for them and that is they are racist.”

In her words, the government’s indifference and targeting of Caribbean-Britons was a grave injustice.

She reminded people that “a man who has spent 50 of his 58 years in England… and was only ever a British citizen” should never have lost his livelihood and benefits in this way.

Others warned of the human toll. Activists like Elwaldo Romeo of the National Windrush Committee asked, “Two years on, why have we still got Windrush people living in dustbins and airports?”.

Labour MP Diane Abbott observed that the scandal had exposed “elements of institutional racism” in the Home Office and called for a “root-and-branch” overhaul. Tens of thousands of people faced the constant fear of being stopped or kicked out of the only home they had ever known.

Government Response and Apologies

By Spring 2018, public outrage grew too loud to ignore. On April 16, Home Secretary Amber Rudd apologized in Parliament for the “appalling” mistreatment of Windrush immigrants. Yet within days it became clear her promises rang hollow.

The Home Office admitted they had destroyed thousands of 1948 landing cards, despite warnings that this would cripple record checks. With no paperwork, even lawful residents had no easy proof of status.

Pressure mounted until Prime Minister Theresa May finally apologized on 17 May 2018, acknowledging the “anxiety” caused. She promised “there will be no removals or detentions” for Windrush victims while their status was clarified.

May agreed to a compensation fund of up to £200 million. Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness, who had pressed the issue, said he believed “the right thing is being done”.

In Parliament, the government pledged that those who had lived, worked and paid taxes in Britain all their lives should never have been cast adrift.

Official reviews followed. In 2020 inspector Wendy Williams led the independent “Lessons Learned” inquiry into the Windrush scandal. She reported starkly that decades of immigration policy had paid “complete disregard” to the Windrush generation.

The Home Office showed “institutional ignorance and thoughtlessness towards the issue of race”, Williams wrote, and the failings were “consistent with some elements of the definition of institutional racism”.

In response, even Health Secretary Priti Patel expressed regret, saying “there is nothing I can say that will undo the suffering of those affected”. But officials insisted the crisis was now resolved.

In reality, many victims saw little resolution. The scheme set up in 2019 to compensate them became its own ordeal. By late 2020, Windrush survivors were publicly complaining of “long waits and ‘abysmal’ payouts”.

Alexandra Ankrah, the senior black barrister in the Home Office team, resigned and accused the process of being “systemically racist and unfit for purpose”.

Human Rights Watch in 2023 concluded that the compensation program was “compounding its injustice”. In January 2023, official data showed only 12.8% of the estimated 11,500 eligible claimants had received any paymenthrw.org. Many who had suffered most waited years with no redress.

The Compensation Scheme: Pledges vs. Reality

In April 2019 the UK government formally launched the Windrush Compensation Scheme for people who had lost out due to immigration status issues.

Unlike the initial UK Settlement Scheme, this fund was meant explicitly for victims. It allowed awards to cover a wide range of losses. These included, among others:

- Banking losses (fees or penalties from bank account problems).

- Daily life hardships (e.g. missing family occasions, travel inability).

- Detention and removal costs (legal fees, travel home, etc.).

- Driving licence issues.

- Employment losses (lost wages or pension).

- Education expenses.

- Health care costs.

- Housing costs (rental or mortgage losses).

- Immigration application fees.

- Living costs (rent, utilities, food, travel, prescriptions).

The scheme was not limited to Caribbean arrivals – any Commonwealth migrant affected could apply.

It opened amid goodwill promises: ministers repeatedly assured the scheme would be fair, open-ended and uncapped. The Compensation Scheme (Expenditure) Act 2020 even granted permanent authorization for payments.

However, implementation faltered.

By late 2023 the Home Office had received 7,688 claims since launch.

Yet only 2,097 of those claims had actually been paid, totaling about £75.9 million.

(Over the same period, roughly £1 billion more was paid on NHS staff and other COVID issues, for comparison.) Alarmingly, the Home Office reported that 53 claimants had died after applying, some waiting years.

Parliamentary scrutiny has been scathing. A 2021 Home Affairs Committee found the “vast majority” of claimants were still waiting, noting the process had itself become traumatic.

One applicant described endless requests for documents and appeals bureaucracy. Officials admit that application times (often a year or more) and low award amounts have left many victims feeling justice denied.

In response to these criticisms, the government modestly extended deadlines and hired support staff, but claimants say progress is too slow.

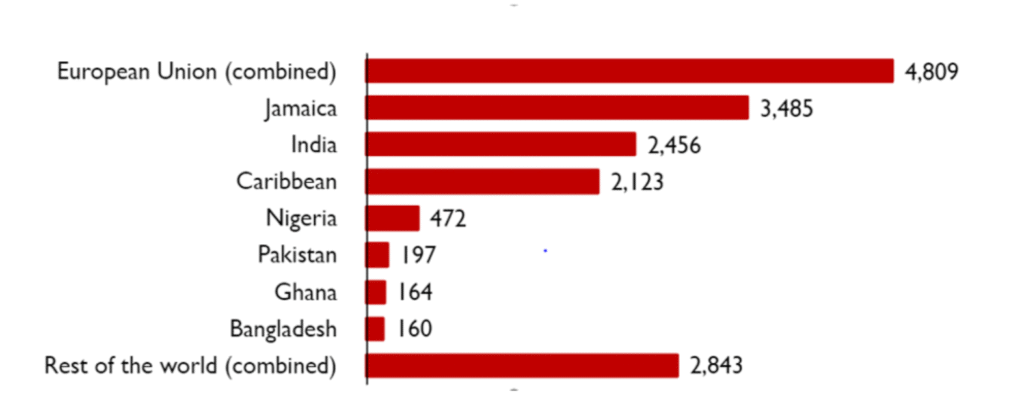

Chart: Approved Windrush documentation by nationality (as of Q3 2023).

Most claims have come from British nationals, reflecting that many victims already had citizenship.

According to official stats, over 16,700 people had been issued new status documentation under the Windrush schemes by late 2023.

Of the claims, 84% were UK nationals (6,476 of 7,688 claims), with smaller numbers from Jamaica, Nigeria and elsewhere.

This underscores that Windrush victims were overwhelmingly citizens or legitimate residents. Still, the statistics reveal lingering hardship: thousands remain in limbo, some too old or ill to wait.

Institutional Racism and Wider Implications

The Windrush scandal has been widely characterized as a case study of institutional racism. Campaigners and politicians argue that the targeting of Caribbean families – while other migrant groups were generally spared – betrayed racial bias.

The Guardian reported Windrush victims noting “race was a big factor” and that “the government’s deliberate attempt to treat some of its own citizens as having less rights” than others reflects racist intent.

The Lessons Learned Review itself commented on “institutional ignorance and thoughtlessness towards the issue of race” at the Home Office.

Critics, including the Runnymede Trust and MP David Lammy, say only a full inquiry into Home Office culture will uncover the roots of these biases.

Some Home Office insiders have agreed. Alexandra Ankrah, who worked on the compensation panel, warned that many staff implementing the scheme had previously enforced “hostile environment” policies, and that the system lacked compassion.

NGOs like Human Rights Watch and the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants continue to press for reforms. Their message: it is not enough to apologize with words if policies and practices remain unchanged.

The Windrush episode has also fueled a broader debate on racial equality in Britain – showing how “Britishness” has too often been narrowed to ethnicity and paperwork, undermining the very ideal of equal citizenship that once attracted the Windrush generation.

The Long Shadow: Beyond Britain’s Borders

The Windrush story has resonances far beyond the UK. In the Caribbean, governments and historians have long demanded restitution for slavery and colonial exploitation.

A 2024 UNESCO commentary by Prof. Verene Shepherd notes that analysts estimate “the UK would have to pay some US$24 trillion to 14 CARICOM countries and US$9.5 trillion to Jamaica” in reparations for the slave trade.

CARICOM (the Caribbean Community) established its own Reparations Commission and formulated a Ten-Point Plan calling for formal apologies, debt cancellation, educational and health investment, and other measures to repair past harms.

These figures and demands dwarf the sums currently on the table for Windrush victims, highlighting how British colonialism’s legacies span generations.

Elsewhere in the former empire, there have been gestures toward justice. In Canada, for example, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau officially apologized in July 2022 to the surviving members and descendants of Nova Scotia’s No. 2 Construction Battalion – the first and only all-Black unit in Canadian World War I history.

Trudeau denounced the “blatant anti-Black hate and systemic racism” that barred these men from combat duties, calling them Canadian heroes. He pledged both acknowledgement and education. In the United States, where the legacy of slavery and segregation still drives debate, legislators have begun laying groundwork.

The U.S. Congress has repeatedly introduced the so-called H.R.40 bill – the “Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act” – aiming to create a federal commission on reparations.

And at the state level, initiatives are advancing: in 2023 California’s governor signed a formal apology for the role of slavery and discrimination in the state’s past. These developments show that the question of reparations is not isolated to Britain – it is part of a global reckoning with the injustices of the colonial and segregation eras.

For the UK, discussions of Windrush reparations have so far been limited. The focus has been on individual compensation and record-keeping, rather than on wider redress. However, many advocates say the scandal has opened a door to deeper dialogue.

Lawmakers like MP David Lammy have argued that beyond compensating victims’ documented losses, Britain should confront the broader moral debt it owes to a community that has been both foundational and betrayed. Reparatory justice, in their view, means education reforms, public memorials, and sustained anti-racism efforts – along with any financial settlements.

As the UNESCO writer noted, “the movement for reparatory justice will continue to grow until justice is delivered to all of those harmed” by colonialism and slavery.

Conclusion

Seventy-five years after the Windrush docked in Kent, the generation it carried has been both lionized and mistreated. The Windrush scandal exposed a bitter paradox: the country that once urgently needed Caribbean migrants turned around and treated many of them as undesirable.

Official apologies and a compensation scheme were belated acknowledgments of wrongdoing. Yet years on, many survivors still await resolution.

The government has paid some £75 million in Windrush compensations, but for thousands that represents only a start.

Those who lived through the betrayal demand more than words. As Dexter Bristol’s mother said in grief, “a man who has spent 50… years in England… should not have his job and benefits compromised… for no other reason than the government’s attempt to treat some of its own citizens as having less rights”.

Windrush reparations, they argue, should recognize not only financial loss but the pain of identity stolen and trust broken. In Parliament, figures from across the aisle agree the injustice “should never have happened,” and that it is right to honour the debt owed to the Windrush pioneers.

Britain’s long march toward justice for the Windrush generation continues. It must encompass both speeding up compensation payments and answering the larger moral questions raised.

The lesson is unambiguous: granting new rights to prevent one group from suffering as the Windrush victims did must go hand-in-hand with addressing the historical root causes. Only when that is done can the promises made back in 1948 – of a home for loyal citizens – truly be seen as fulfilled.

This reporting about Windrush Reparations draws on a wide range of trusted data..All information in this report is drawn from primary and secondary sources, including investigative journalism, official documents, NGO reports, academic studies, and direct testimonies. Below is a list of cited sources for verification.

British Museum / Royal Museums Greenwich – Story of the Windrush Generation

The Guardian (various Windrush coverage and interviews)

Human Rights Watch – “UK: ‘Hostile’ Compensation Scheme Fails ‘Windrush’ Victims” (Apr 2023)

House of Lords Library – Windrush scandal and compensation scheme (Feb 2024)

UNESCO Courier, “The Caribbean calls for restorative justice” (Aug 2024)

UK Parliament Hansard – Windrush 75th anniversary debate (July 2023)

U.S. Congress (Library of Congress) – H.R.40 summary

The Guardian – “Theresa May apologises for treatment of Windrush citizens” (Apr 2018)

*You May Be interested in Reading this investigative piece by the same author, “Uyghur Detention Camps: Unmasking the Machinery of China’s Repression“.

*Learn More About The Author Here.